The culling of late-night Radio Scotland

…I was tuning in the shine on the late night dial

Doing everything my radio advised…

Elvis Costello

It’s just over ten years since I broadcast my last show on BBC Radio Scotland, bringing to an end a 20 year relationship with the station which took me through early morning, mid-morning, afternoon and late night shows. I left of my own accord, or to be precise at the behest of two heart attacks and the consequent period of panic and recovery. Which is still ongoing.

When the cardiac calamity struck I was broadcasting three nights a week in the week’s-end slots that will be relinquished next month by Billy Sloan and Natasha Raskin Sharp and held onto by Ashley Storrie. You can read the blog I wrote in 2015 here.

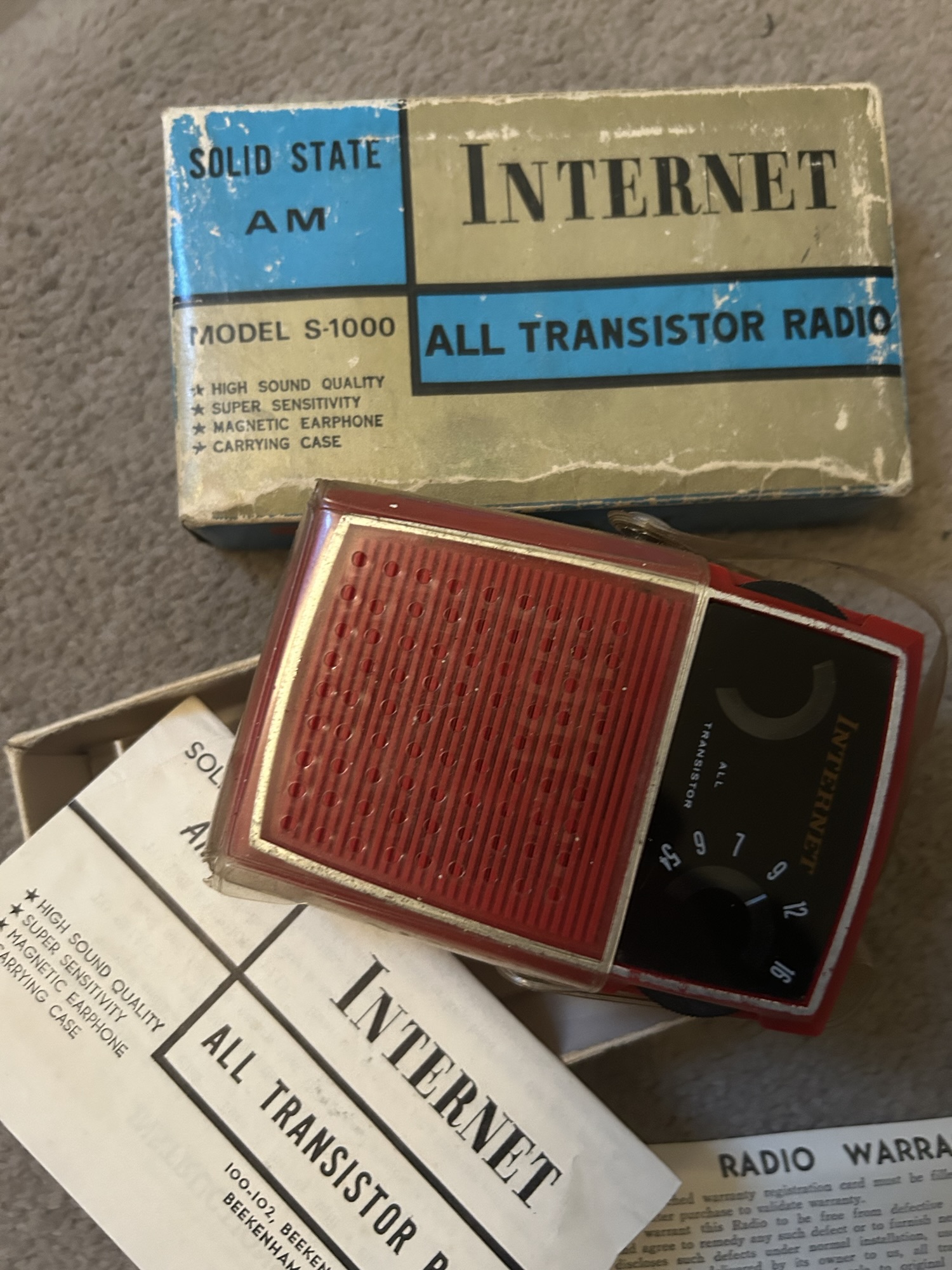

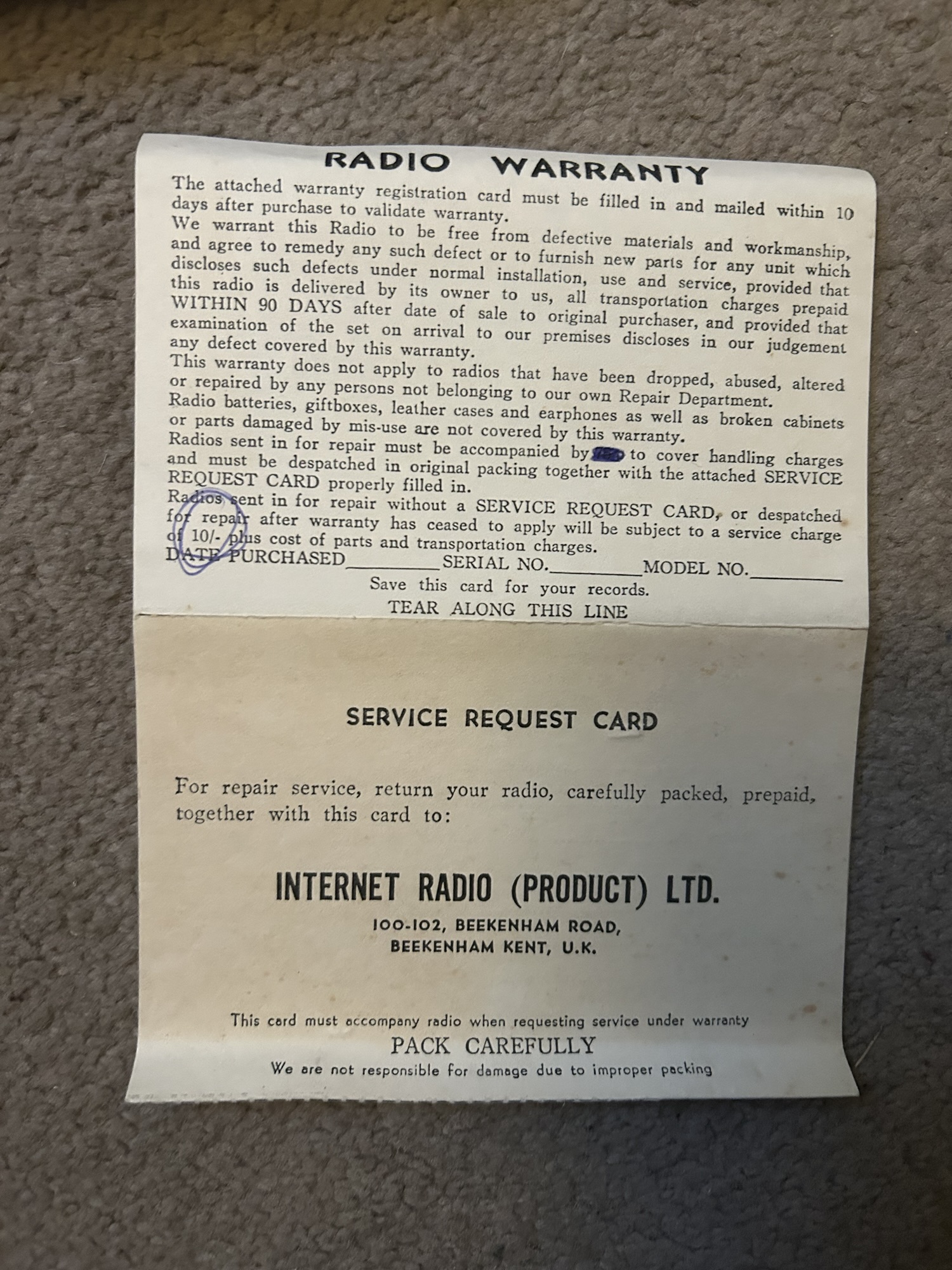

Of course, that was when radio was still radio. Now it’s officially ‘Audio and Events’, and no show is complete if it’s sound alone. It’s all high-definition video creatures nattering in front of (for some reason) those big Shure SM7B microphones. Everyone wears headphones. But you can tell they’re really rehearsing for TV, or TikTok, or YouTube, or I’m a Treacherous Celebrity Influencer Get Me a Free Kebab.

It’s not about listening, it’s about consuming. The listeners have departed. And the consumers must be fed, mostly with second-hand fame or reassuring pop pap.

Back in 2015, Iain Anderson was handling the earlier part of the late-night week, though a youngster called Roddy Hart was about (or had just started) to do stand-in stints for him. These 10pm-1.00am, later 10pm to midnight shows were produced for the BBC (and still are, other than I think the Friday night Ashley Storrie gig) by independent companies Bees Nees and Demus and from 2013 represented, for BBC executives, an easy and relatively cheap way of fulfilling a corporate obligation to ensure a certain proportion of radio production went to the Scottish private sector. Just as River City (also cancelled) was born as “a job creation scheme for Scottish actors”, to quote one of its progenitors. Several non-pensionable, non-Beeb staffer livelihoods therefore depended on those late night slots.

Billy Sloan, after a long and storied career at the Daily Record/Sunday Mail and Radio Clyde, had been standing in for me for a while and when I dropped out initially took over on his own, produced by Nick Low and his team at Demus. Eventually the changes came which brought in Natasha Raskin Sharp and Ashley Storrie.

It’s fair to say that all the shows were meant to be accessible to and representative of the Scottish musical community, featuring local artists as well as providing the kind of late night listening expected of…well. A more mature demographic. I was 59 when I stopped broadcasting (70 on Hogmanay, send statins). Most of my listeners were old enough to remember the Apollo’s bouncing upper circle. That Mick Jagger wasn’t just somebody in a song by Christina Aguilera and Maroon 5.

And that may be one of the problems, although I’m not sure it’s the main one. Iain is in his mid-eighties and Billy’s maybe a few months younger than me. Roddy and Natasha are mere whipper-snappers and the production teams are comparatively youthful too. But for the new-broom Pacific Quay executives like incoming ‘head of audio and events’ at BBC Scotland, Victoria Easton Riley, it’s not so much the mooted reduction in demographic age from 55 to 45 (less close to death, which is never good for audience figures) as a need to spray her Bauer-radio-nurtured sheen of commercialised glossiness on the schedule. And who cares about all those awkward, spiky wee bands from Greenock and Lugton anyway, when the Swifties are baying for more Red? It’s a policy change.

I don’t wish to sound paranoid, or God help me, nationalistic, but I suspect this is coming from London. The Powers That Beeb want increased listening figures, a more corporate feel, not so much of a God’s Waiting Room vibe. Less radio, more audio. And yes, fade down the Scotland thing. In the last days of Jeff Zyciniski’s rule as a proper head of Radio Scotland, there was a pilot project to provide a digital ‘Radio Scotland 2’ channel which would complement the terrestrial one, providing a much broader range of programmes rooted in community needs and aspirations and a deeper delving into the creative life of the country. That came to nothing when Jeff left. Too, well, Scottish. Now, perhaps, a more commercially viable model is being sought for the BBC in its entirety. Because the continued licence fee system is all but unviable, politically and economically, and in the world of Netflix, Amazon Prime, Apple, Disney and Sky, the days of public broadcasting are numbered. You can see that in the willingness to capitulate over Trump’s ridiculous threats of punitive legal action due to one bad edit. And in the very existence of BBC Commercial Ltd and its subsidiary BBC Studios.

At the personal level, though, the Radio Scotland changes will be very hard, notably on the presenters losing their fees of several hundred quid a show, and the producers who will be looking for work in a market which is very far from expanding. Maybe there will be Substack and Mixcloud versions of the lost shows, but from experience I can say that these are hard to maintain and financially difficult for all concerned. I hate all this begging bowl Patreon-Go-Fund-Me stuff. Subscriptions? There are too many demands on our digital wallets. And artists will not receive their £20-or-£30-a-pop Performing Rights Society Payments every time their records are played. That little financial boon for Scotland’s songwriters and performers is featuring a bit too much in the vociferous public complaints being made by aggrieved singers and bands, I’m afraid. It’s an anomaly and given the very small listenerships for the late night shows, it’s arguable that those payments are way higher than justified. I also remember stories about a request show where drunken emails and texts demanding airplay for a particular track were being made by the royalty holders, determined to raise the price of a few more pints…

How low is the listenership? One petition calling for the BBC to rethink the changes apparently has 10,000 (digital) signatures. That’s fantastic, but far more sets of ears than any of those shows actually and consistently pull in. I could tell you about one broadcast during which the presenter, unaccompanied at the time by a producer, fell sound asleep in a Pacific Quay studio leaving a gap of several minutes when records should have been playing and incisive chat beaming to the nation.

Nobody noticed. Because deep in the podcast-infested night, the sad truth is that very few folk are listening to Radio Scotland. Sometimes just the bands who’ve been told in advance that their record is going to be on.

And it’s not just the money. For a presenter, giving up broad-, or narrow-casting is hard, especially if it’s been your life for many years. That sense of connection and community, of having an audience, has gone, and you need to find a way of filling those mental and emotional gaps. You don’t just lose your job. You lose part of your identity. Your passport to other gigs. More than anything, you lose your voice.

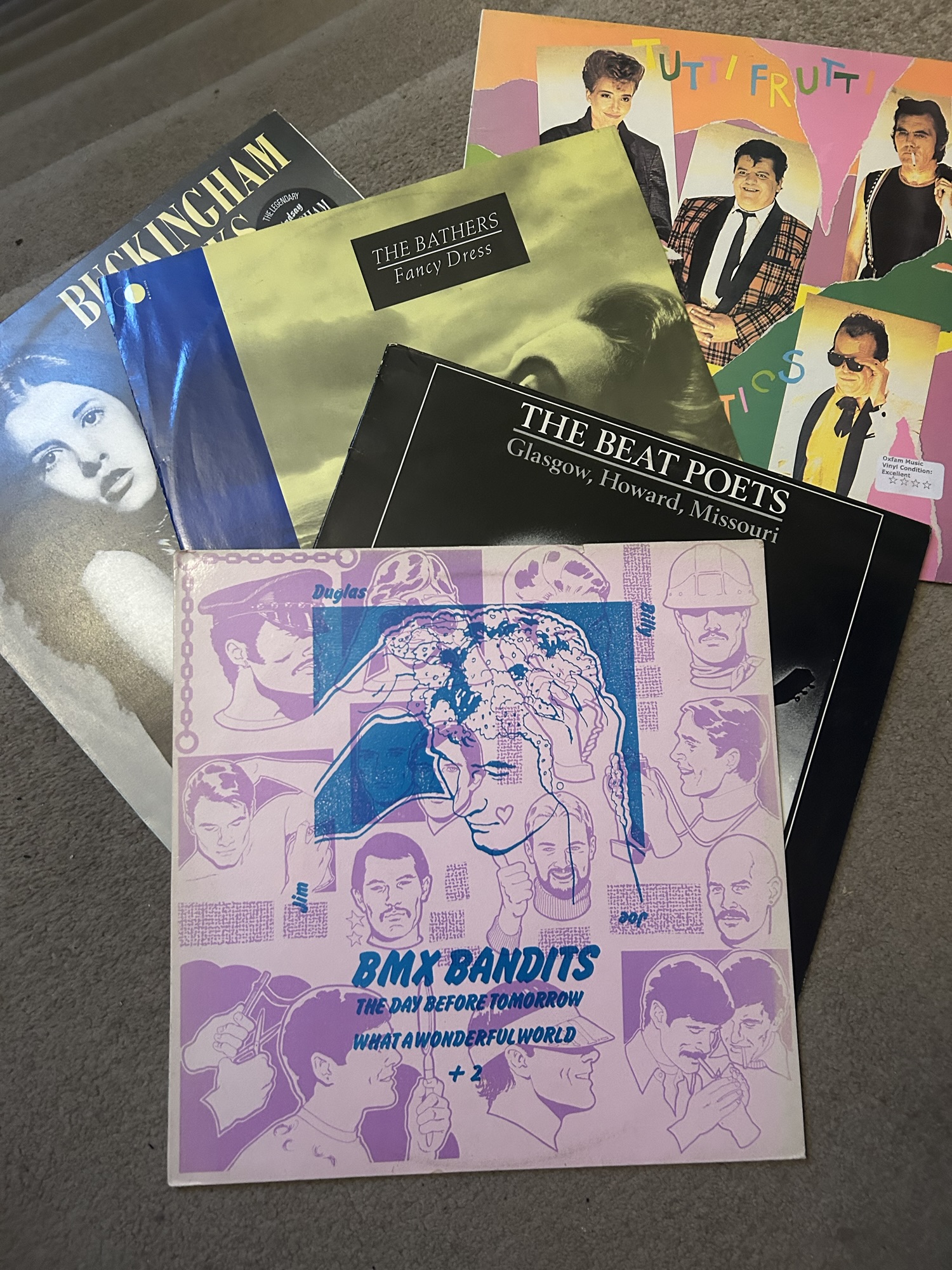

I found that a dog (or two) helped. Though what Rug the St Bernard and Hugo the Segugio Italiano made of Sam Cooke Live at the Harlem Square Club, Nyah Fearties and Junior Wells blasting out of the speakers I’m not at all sure. That’s one good thing about not being on the radio. You can play what you really like. Even if it’s only for the dog.

Meanwhile, there are a few corners of BBC Radio Scotland where informed presenters and producers still make radio shows that reflect community needs and passions. Where specialist programmes playing blues, country, hard rock and metal (never featured on mainstream bourgeois Beeb) indie and folk all feature. That would be Radio nan Gaidheal, Radio Orkney and Radio Shetland, the last remnants of BBC community opt-outs in Scotland. Mess with them, Victoria, at your peril.

I was seriously thinking about hiding the receiver

When the switch broke ‘cause it’s old…

Leave a comment