This is one of the essays I wrote to accompany Stewart Cunningham’s pictures in our wee book Big Rhythm: 1980s pop snapshots from Scotland. Too late to get a copy I think now before Christmas, though I have one or two with me on the south side of Glasgow and I think Stewart has a few left in the West End or in Helensburgh.

I should say that all of the copies posted from Shetland last week were sent as ‘second class, large letter’ and there were delays due to weather. Apologies, but they should all have arrived by now.

Glasgow in the early 80s was awash with talent and ambition, not necessarily in the same musical packages. The city was not, despite the slogan, Miles Better, though God knows, it wanted to to be, was desperate to be. My ‘proper’ job was as a journalist for a building trades newspaper, before TV beckoned, and our watching brief at Project Scotland was the redevelopment of Glasgow with schemes like GEAR (in retrospect an unfortunate acronym) which stood for Glasgow East Area Renewal.

This was at a time when Iain Mackenzie’s Café Gandolfi was almost the sole outpost of bohemianism east of the City Hall. The so-called Merchant City had yet to sprout its cappuccino trees and croissant machines. Far from the multilevel restaurant complex it now is, the Gandolfi was for Glasgow a unique space, the Tim Stead furniture and monochrome photographs providing a haven unlike anywhere else. You could get proper coffee, decent beer, delicacies such as sliced apples dusted with cinnamon and served on plain digestive biscuits. Unfamiliar cheeses like, well. Boursin. Billy McAneney would graduate from there with Iain to open Baby Grand at Charing Cross, before Iain moved further west with the North Star in Queen Margaret Drive. He was an absolutely crucial figure in the development of Glasgow’s food and drink culture..

East end bands were not so common, though I think the Lone Wolves, fronted by James King, were an exception. Stewart never photographed them, but they were the most intimidating and perhaps my favourite of all Glasgow’s 80s bands. Feared and disparaged by some, they took no prisoners on or off stage. Brilliantly uncompromising. James an unholy combination of Lou Reed and Hank Williams amidst the crunchy jangle of the Flamin’ Groovies.

To quote one knowledgeable pal: “My favourite band of that time. They were regarded as having an almost mythical quality, quite deservedly so. The best band that never made it big.”

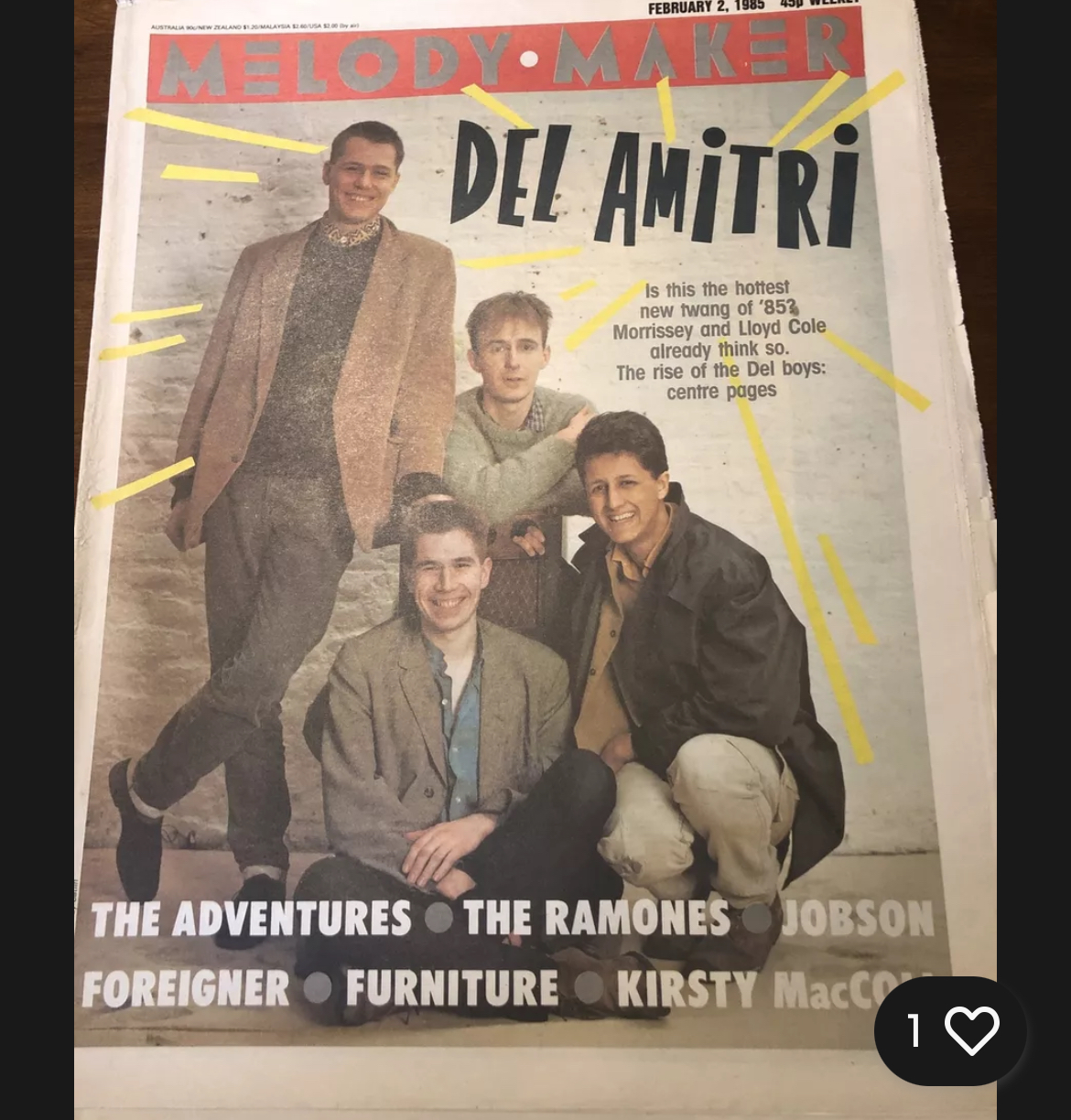

And the Lone Wolves were, or at least seemed genuinely working class at a time when most of the 80s crew were distinctly and obviously Bearsden-bourgeois (Del Amitri and Lloyd Cole being examples) or at the very least from solidly respectable employed and aspirational households. While sometimes proudly trading on Glasgow’s reputation as a deprived and violent city. I’ve always found the title of Bobbly Gillespie’s memoir, Tenement Boy, amusing. The tenement that denizen of the Boy’s Brigade came from was an extremely nice one on the south side, his dad a legendary national print union officer and would-be Labour MP.

Suffering city

Money, and the desire to get hold of some was key to the whole Glasgow scene. Remember, this musical theatre was being played out to a backdrop of extreme poverty as the heavy industrial heritage of west central Scotland was trampled beneath Thatcher’s midrise heels. We might have been out at Henry Afrikas trying to pick up nurses on a Wednesday, fuelled by softpack Marlboro fags and continental beer, but the city was suffering. You just had to head out to Paddy’s Market on a weekday morning to see how far down folk could find themselves. At first it was shocking to see elderly men shaking from the DTs, wearing flat caps, sports jackets, ragged shirts and stained ties, crouched over spread dishtowels containing their entire earthly possessions – a lighter, a stray book, a shirt, a pair of shoes – for sale so they could get just one drink. But it was the same day after day.

And there was violence too, the kind of instantaneous flareups that you see best portrayed in some episodes of The Sopranos, or in Peter Macdougall’s Just a Boy’s Game. One night in The Griffin, a peaceful table with two couples sitting there suddenly erupted in a hail of flying glasses, broken bottles punched into faces, blood and screaming. And stuff like that affected the music scene too, which of course attracted the odd gangster with cash and glamour in their eyes. Some went on to eminence in that field.

Amid all this came the A&R men and women, ‘Artists and Repertoire” record company and publishing scouts keen to snap up the best or at least the most commercial of the acts available. Even hacks like me were offered finders’ fees (which never emerged) or were tempted into management. I crave forgiveness from Wee Free Kings and Rattling The Cage. We should all have known, and done better.

Advances were compared, contracts copied and distributed like samizdat propaganda (“tell no-one..tell everyone…”) The numbers of record company people on a guest list became a sign of impending success, of hype, though the all-time record, I believe this was 33 for Goodbye Mr Mackenzie, then managed by Elliot Davis of Wet Wet Wet fame, cat food and fortune, at Fury Murry’s.

A&R frenzies

I was at that gig and the band were inevitably overwhelmed. Backstage beforehand I drew looks of venomous disgust from Shirley Manson, then only about 16 and playing keyboards, when I told her that I knew the minister of her family’s Kirk.

The record company scouts tended to stay at the Holiday Inn, and the bar there became a post-gig hangout for all and sundry, drink flowing from the purses of CBS, Phonogram, Virgin and occasionally American publishers and companies like Geffen. There were some weird encounters. One A&R guy kept turning up in Glasgow in pursuit of a (now very well-known) female singer. After his liaisons, he would call me for details of some band he could tell his bosses he’d been to see. Expenses to claim.

Bribes? For good reviews or writing a feature? No, that didn’t happen, though I was flown to London and Madrid by record companies for features that never, in the end, materialised. Always bite the hand that feeds. I once saw a legendary promo guy buy drinks for every customer in Bannerman’s in Edinburgh’s Grassmarket . He was desperately trying to boost a feature written by me about…I can’t remember who.

Leave a comment