The three freemasons got on the Glasgow train at Reading, sat in front of us and immediately began talking, loudly about their Lodge and how one of them (young, frisky, wearing, of all things a Freemasonry sweat shirt) could progress through the various hierarchies of masonhood from Junior Deacon to Senior Deacon, Warden and everything masterly beyond. Well, two of them did, while knocking back large quantities of Avanti West Coast ale. The other was slumped and clearly in that hungover condition of sleepiness that obviates the need for more alcohol.

I thought about my great-grandfather.

The miles trundled past on the way to Preston, or possibly it was Hogwarts or King Solomon’s Mines (I was getting confused by this point), where they got off, the conversation having moved into intimate discussions of sex, marriage and comparison between various lodges in the same way folk might talk about the quality of football or bowling clubs.

I was, it’s fair to say, surprised. Freemasonry has clearly changed, grown noisier and less discrete since the days of secret handshakes and the absolute family denial that my great-grandfather had risen through the ranks of Master and Master Mark to the extravagant mysteries of the Royal Arch. Before dying in 1917 at Gogonyo, a remote part of what is now Uganda, suffering from ‘Blackwater Fever’. George Morton was 43.

He was buried by the men who worked for him at the British East Africa Company’s Gogonyo ‘cotton gin’, far away from his beloved Lodge St Andrew (465) in Glasgow. His son, Tommy, was born in Africa, returned to Britain and joined the RAF as an NCO pilot. He trained as an engineer, and was killed in a pithead accident in 1938 when my dad, also George, was just a wee boy, at the Rosehall Number 5 coal mine in Coatbridge, Lanarkshire.

For a BBC documentary in the early 1980s, I became the first person to go through a re-enacted masonic entrance rite on TV. First non-mason, I should say. At the time, this was quite shocking. The details of the rite itself had to be pieced together from various hard-to-find books and reluctant interviewees, and some members of the film crew were very unhappy about the whole project. For several years afterwards I was getting knowing glances and thumb-on-knuckle recognition signals from the most unexpected people.

That was Scottish freemasony, though, which was, at least in the old industrial heartlands, both a serious business and a rough and tumble piece of male socialising and professional advancement. Sometimes protection and security too. But the point was, it was secret. You certainly didn’t talk openly about the Lodge on trains. There were no embroidered sweatshirts, cheery open evenings for wives and bairns.

But things have changed, you will find cheery Master Masons galore being interviewed online about the good works done by the Order and how there’s nothing sinister about this rolled-up-trouser-leg stuff at all. Masons have to declare their membership on the public record if standing for office, and I have to admit to some surprise at the members of the Morton Lodge in Shetland (no relation) who were also Shetland Islands Councillors. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been.

The “Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland” has a rather slick website where you can click on a button and, if not automatically join, begin the process that culminates in initiation.

“Scottish Freemasonry is a community of like-minded individuals committed to personal growth, mutual support, and making a positive impact in our communities,” runs the somewhat bland ‘content’. “We are proud of our heritage and dedicated to fostering a spirit of unity and respect among our Members.” An unfortunate, moody photograph shows a group of youngish men in black suits, posed like a still from Reservoir Dogs.

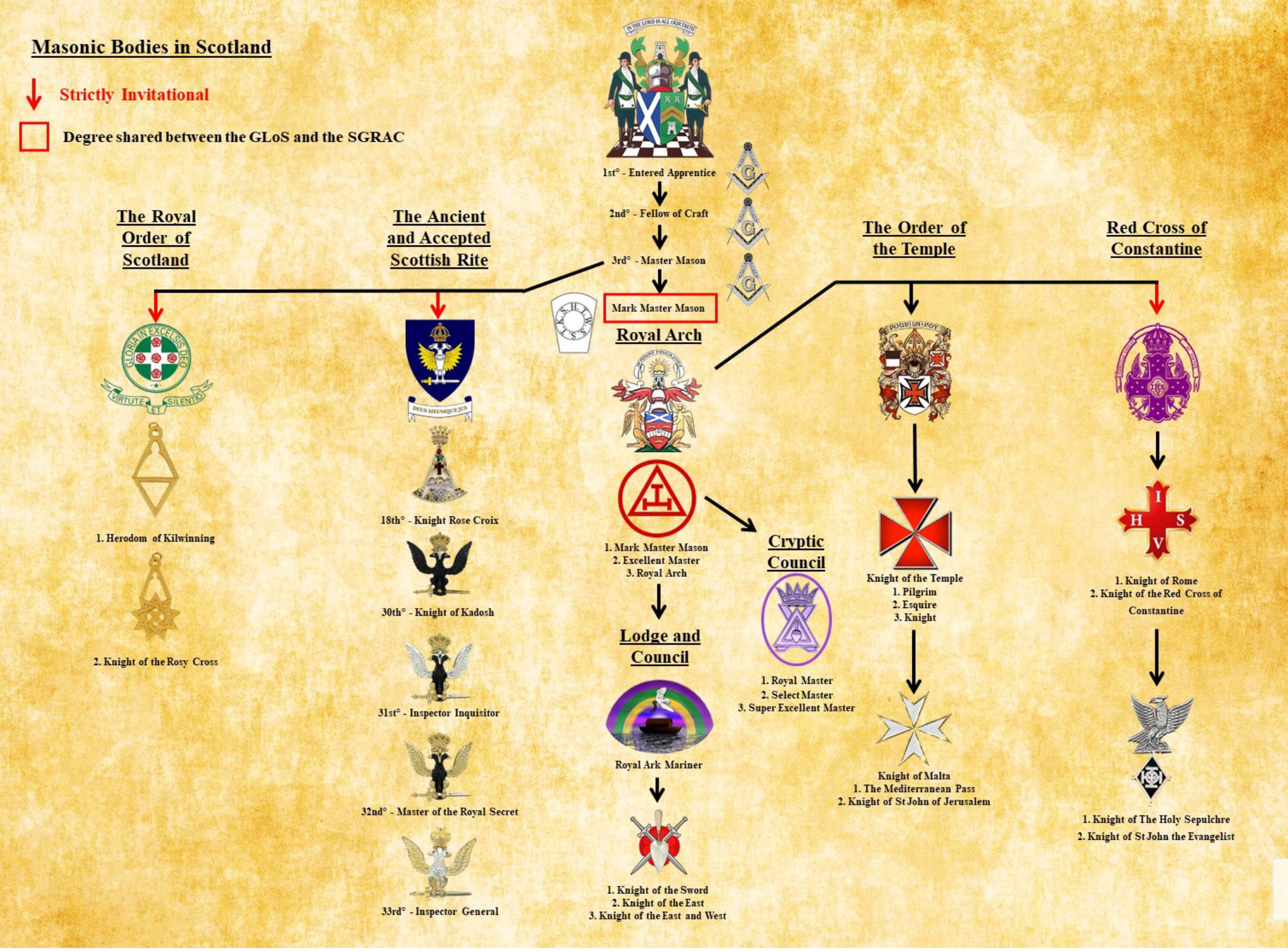

Freemasons’ Hall in Edinburgh is, to say the least, ornate, and the online vibe is one of grandeur and power; while there is a rather formalised, cautiously polite invitational aspect, it’s strictly males aged 18 or over. And then it all gets complex, not to say bewildering. Because there are various “Masonic Bodies in Scotland” and then there are “masonic Bodies in Amity with the Grand Lodge”, including some “not permitted to operate in Scotland.” A few who may indeed print their own sweatshirts and chatter very loudly on trains.

You can hire Freemason’s Hall in Edinburgh for an event, though presumably there are limitations as to the nature. No punk rock gigs. Most Masonic halls are available in my experience for community uses of one sort or another, from creches to parties, though I remember being somewhat dumbfounded by the sinister goat’s head peeking from behind the (incredibly cheap) bar in one remote Ayrshire establishment hired by BBC Radio Scotland.

Edinburgh is very grand grand lodge stuff, though lodges in the old mining communities of nearby Midlothian will be a different story. As an Ayrshire lad, I’ve always been fascinated by Lodge 0, Kilwinning, “the mother lodge of Scotland” or “heid lodge”, which is thought to date back not to the 18th century as the Grand Lodge in Edinburgh claims for itself, but to the formation of Kilwinning Abbey in 1162 or thereabouts. Just a mere 600 years older. There has in fact been bad blood in the past between Kilwinning and the Grand Edinburgh Lodge, Kilwinning declaring unilateral Grand Lodgedom, but this was settled in 1807 with the admission by the Embra folk that Kilwinning deserved premier status. It’s thought both Robert the Bruce and King James the First both participated in Masonic rites at Kilwinning. It’s a place of pilgrimage for masons worldwide.

What’s fascinating is that freemasonry in Scotland is thought to have been planted by itinerant workers from mainland Europe engaged in building Kilwinning Abbey in the 12th Century. These highly skilled men were free to travel, the very best freelance workers bringing their skills to bear on ecclesiastical buildings throughout the continent, hence the title ‘free masons’. They passed their skills, secrets and craft rituals on to Scots working alongside them, and so Scottish freemasonry was born. Kilwinning Abbey was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and St Winning. Pre-reformation, so those masons were Roman Catholic, just like everybody else…

So there we have Freemasonry in Scotland, borrowed from immigrant workers benefitting from European freedom of movement. I can find no record of the ‘heid lodge’ opposing Brexit, but it would have been understandable…

I’m guessing, though. Some things are still hidden.

The “Mother Lodge” (interesting, that female genderisation) has a fascinating website and to my delight there is an online shop where you can buy key rings, badges, books, tie-pins and other masonic memorabilia.

No sweatshirts though. And I’m wondering, Gogonyo, in Uganda, Pallisa district, where my great-grandfather was buried in a plot, according to a letter home, surrounded by a planted fence of trees…did he, an immigrant from Scotland, start a wee masonic lodge there? That’s a secret.

Note: I’ve changed the train boarding station and destination for my three freemasons. Probably best that their indiscretions remain anonymous…

Leave a comment