The rotting of whisky

Out for an (excellent, but teetotal) meal the other week I looked speculatively at the hotel’s vast collection of single malt whiskies, many bottles nearly empty or half-empty. As many had been last time I visited two years ago. And I thought about how whisky is like petrol.

There are different varieties of petrol. Different qualities, origins, grades. But they’re all functional refinements of crude oil.

Whiskies are flavoured alcoholic beverages designed to get humans drunk, often inefficiently made and aged. In those inefficiencies are the ‘qualities’ so appreciated by so-called connoisseurs. Who are, let’s be honest, mostly drunken chancers, clowns and lovers of descriptive language. Like me.

Leave unleaded petrol in your lawnmower over the winter and there’s every likelihood it won’t start. Because petrol goes off.

So – eventually- does whisky. Or at least it changes in flavour. It’s simple chemistry. Air in the bottle. A broken seal. Oxidation and evaporation. It’ll still taste like ‘whisky’ (burnt trainer insoles: you can learn to appreciate it) but the distinctive reek of cask and distillate will be diminished. The truth is, you should never order a single malt in a bar unless you know it’s either been opened recently or the dram is labelled and price adjusted with regard to the date of its opening. The only place I’m familiar with that does this (along with an annual, heavily discounted shelf-clearing party) is Fiddlers in Drumnadrochit.

And at home, in my latter days of drinking, I wouldn’t buy a bottle of whisky and open it unless it was going to be drunk within…well. Let’s say six months. And a maximum of two unsealed bottles open for guests (and myself) at any one time.

Sometimes, in my case fuelled by a daily diet of strong anti-death drugs, your taste for whisky goes off too.

There are still a few funeral whiskies secreted away unopened for consumption at my wake. The Jim Clark 50th anniversary Aultmore, the sample of Mortlach 70, the Pulteney 30. Once all attempts at reviving my corpse using them have failed.

Welcome to Loch Slump and the Water of Sobriety

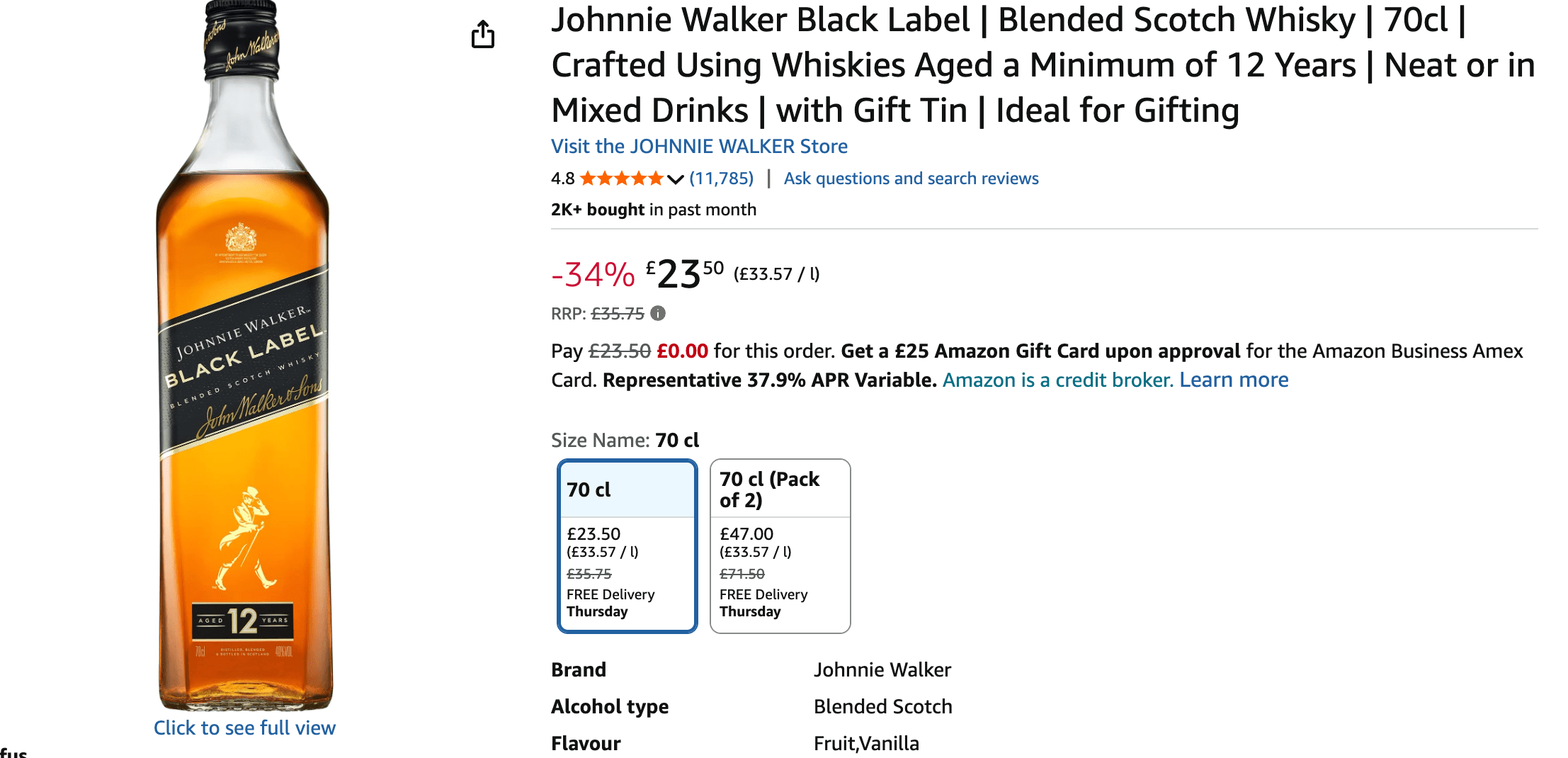

For a while, sickened by the ridiculous posing, posturing and alcoholic pontificating of the whisky industry’s professional evangelists (of whose number I once counted myself) I abandoned drinking malts altogether and contented myself with the thinking drouth’s everyday dram: Johnnie Walker Black Label. It was the sudden availability of that consistent and well-made glug of corporate Diageo spirit for an astonishing £20 a bottle online, that prompted me to wonder what was going on? In these inflationary times, why was it so cheap?

Turned out it wasn’t just Diageo who had a loch-sized puddle of liquid to get rid of.

Prices have been falling right across the board, tumbling like World Whiskies Awards judges on a London pavement. Because basically, the whisky bubble has burst.

This is extremely unfortunate for the entrepreneurs who have been busy over the past decade raising money to open new distilleries and with even the mighty Diageo suffering financially. Scotch whisky is dealing with a crisis in oversupply as export markets fall (notably in the USA, with the added issue of Trump tariffs) the Covid-fueled upsurge in tomorrow-we-die drinking falls off a cliff (we’re not going to die after all, or at least not yet) and Gen Z moves with some alacrity towards drinking all forms of alcohol less or not at all.

Because now we know. There is officially no safe amount of alcohol. Not even ‘te bheag’ (a wee one) is good for you. The French mythology of a healthy litre of red and two armagnacs every day (for breakfast) has been debunked. The dram is over.

Breweries are closing as well as distilleries. The Great Gin Idiocy is at last diminishing, as people realise their supposedly artisan brands are just flavoured alcohol and they all taste the same with tonic. Vodka is going for screenwash. And while whisky distilling will survive in Scotland, the ageing necessary before whisky can be sold (minimum three years, anything from eight to Methuselah) means that it will take a while for the industry to recover. Expect more closures, new businesses going to the wall or big Chinese concerns moving in to hoover up the scraps.

More non-drinkers. A non-alcoholic pub has just opened in Aberdeen. It’s called Sobr and I pray they do draught Guinness Zero, which is better than the real thing.

Cask strength bargains galore!

But all this does mean that for the lowly, unregenerate or backsliding toper there are bargains to be had. And having spent decades learning to tell the difference – professionally – between Lagavulin and a belt in the face with some Glen Befuddled, I recently found myself slipping, spiritously if not spiritually.

I bought a bottle of Laphroaig 10 year old cask strength (58.5per cent alcohol), reduced from £75 to £45, and the supermarkets are full of other such snips. Even cask strength independent bottlings are available for a song, or the price of Taylor Swift’s new album on vinyl.

The first cask-strength whisky I ever failed to taste was called As We Get It. It was in the back bar in the St Duthac Hotel in Tain, 1988, and I’d just finished a gig as part of the Tennents Live initiative to conquer the Highlands of Scotland for rock’n’roll. Or in my case, sarcastic acoustic folk.

I failed to taste it because it nearly killed me.

Got by As We Get It

We were relaxing, post-performance, when the barman produced the (unopened) bottle. At that stage JG Thomson, who owned the ‘As We Get It’ brand, were permitted to say on their plain white labels where the spirit in the bottle had come from – and this, in fairly small print, stated that the whisky (deep, clootie-dumpling-brown stuff) was “distilled by Macallan-Glenlivet PLC”. Not that I was allowed to look at the label. A half-tumbler of cratur was poured and I was urged to drink. I slugged, swallowed and nearly choked to death as the 102-proof (58.4 per cent alcohol) incinerated my palate and stopped me breathing for at least a fortnight. Much back-thumping, water consumption and emergency hilarity ensued. And when the St Duthac stopped spinning, I was ready to dilute and consume some more.

Sold as ‘pure malt’, which is a catch-all term implying only that the whisky is made ‘purely’ from malted barley, As We Get It in those days (the brand has changed hands and style since) was a very rare example of a single-cask bottling. Most whiskies then were bottled at 40 , sometimes 42 per cent alcohol, diluted with whatever water came to hand at the plant. As We Get It was (probably) not sooked’n’savaged by ‘chill-filtering’ and as near to the wood as could get in a pub glass. No age specified. It was extremely difficult to, as it were, get, and Macallan were not at all happy about their hallowed name appearing on someone else’s label. There were very few ‘independent bottlers’ in those days and Macallan were particularly protective of their intellectual property.

Single malt whisky had yet to attain the super soaraway cultural fashionability and fiscal success of the 1990s. Even in 1994, when we made the TV series based on my book Spirit of Adventure: A Journey Beyond the Whisky Trails, the effects of the Great Whisky Slump of the 1980s were still seen in closed distilleries and poor availability of single malt bottlings. Even advertising spirits on TV was forbidden by law. Hence the open arms with which our STV crew was welcomed at every distillery we entered and stumbled unsteadily out of.

Cask strength whiskies and rare bottlings became, for me and for a time, habitual. I could claim for whisky on my tax returns. I remember playing Trivial Pursuits at Skeabost House in Skye, the prize being a dram of 1955 Talisker. In the Gordon and Macphail warehouse in Elgin, a small quarter-cask of Ardbeg, distilled in 1974 and later bottled under the connoisseur’s choice label had its bung loosened and a ‘spill’ slopped into my cupped hands. That was magical. Now, you’d pay £1500 for a bottle, if you could find it. And for that matter, about the same for an original As We Get It.

Buying a cask-strength whisky of slightly more recent vintage, though, is currently easy and you can get some amazing deals. For £54, tempted beyond sobriety and Islay, I bought a bottle of 100-proof Highland Park, 14 years old, part of the Signatory ‘vintage’ range. If you go to the website of Aberdeen dealer The Whisky Barrel, there’s a whole range of sub-£50 single malts, including other Signatory cask strengths. No payola, by the way.

The end of the affair

So I poured a smidgin of said Highland Park and added water to make it non-fatal. Sniff: smells like sideboards, carpets and burnt tyres. Taste: nippy. Like siphoning burning petrol mixed with TCP and Dettol. Or was that the Laphroaig? I estimate that maybe three years ago either bottle would have cost at least £100.

Anyway, a blinding headache and aching teeth ensued. And I remembered why I stopped drinking whisky in the first place:

It’s a functional mix of burny chemicals that inebriates, attacks and destroys body and brain, and at the very least leaves you feeling like shit.

Crack tours of Colombia! Distillery tours of Scotland!

It’s Scotland’s pride, economic bulwark and death-dealing misery. It’s as if Colombia celebrated cocaine with a touristic Crack Trail of production centres. Trace the production of Fine Colombian from coca to Steely Dan! Sample our range. Pink, black, white? Never freebased? Now’s your chance! Our range of Escobar merchandise is very reasonably priced…

So yes, the whisky bubble has burst.

And so has my last lingering affection for the stuff.

Fancy a coffee? I have some Kopi Luwak Coffee Civet Weasel 100% Pure Roasted Vietnamese Coffee Beans, and a Rancilio Silvia. Add some Tesco decaf instant for balance. No hangovers! And the old Royal Enfield seems to run fine on Highland Park. As long as it’s cask strength.

.

Leave a comment